Seoul, February 23 – April 29, 2018, http://ilmin.org

The three floors of Ilmin museum contained three mini-solo-shows by three successful mid-career Korean artists.

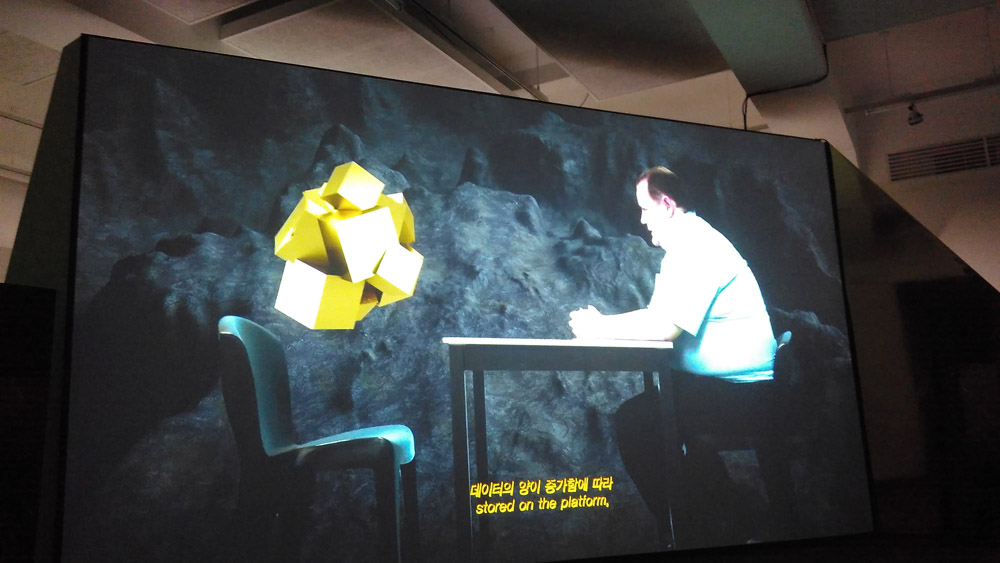

On 1F Ayoung Kim김아영 presents Porosity Valley. The centerpiece of the show was a large projection with a short film utilizing post-internet aesthetics, reminding me of Lawrence Lek’s Sinofuturism or Christopher Kulendran Thomas’ New Elam. The film told a story of a virtual entity being data-migrated from one location to another, playing on real-world migration issues, and merging them with an otherworldly virtual world. The 3D modelling was quite crude, not attempting to “simulate” anything, and rather letting the viewer’s imagination do the job: the virtual entity was represented by a simple arrangement of floating rotating cubes mapped with a golden texture. Overall the film did its job, and it was able to produce emotions and a push towards making the spectators think about the data/memory/migration etc. concepts. Besides the video projection, the room looked quite bare, and the few render printouts hanging on the dimly lit walls could not improve this feeling. The video was worth seeing, but the sparse installation made the whole thing look more like one video artwork and not like a solo show as proclaimed.

2F was reserved for Lee Moon Joo이문주, a painter. This floor was the only worthy of the solo show description. It indeed contained an array of paintings by Lee, large and small, accompanied by a documentary section. Lee’s topic is the building up and destruction of architectural structures and landscapes, one could call it the architectural consumerism: Buildings are built up, only to be torn down a few decades later because “the times have changed”. But basically in order to allow more money to be spent. Lee creates painting-collages that combine different views of construction sites with, for example, sightseeing busses and boats, signifying the obsession with seeing/consuming new products, images and landscapes. I could recognize some locations in Berlin (the Palace of the Republic being torn down and O2 arena being built.) and it looked like a nice documentation. The exhibition text suggested a “critical approach” toward the “repetition of decline and renewal in many cities built on the basis of globalism and global capitalism”, but I wondered, why this had to be painted and not for example photographed. Painting somehow solidified the verbalized issues in a highly aesthetic form of an artistic product, that has a quite similar life expectancy as the buildings that it was talking about: The painting is a product, expected to last eternally, but in fact, the following few decades will decide its course, whether it will survive or be scrapped. The painting is part of the consumption cycle in the same way as the buildings are. Of course one could argue that everything is. But painting are the most “objectified” form of artwork for me, which makes it a bit paradoxical when it is used for a criticism of objectification, without acknowledging the message of the medium itself. So I felt some conceptual “cognitive dissonance” here.

3F was Jung Yoonsuk’s 정윤석 Lash. As with the 1F, it felt more like one piece than a show: A two-channel documentary video from a (probably Chinese) factory producing life-size sex dolls. The seductiveness of the image was the main attraction of the work: Hands touching artificial skin, pushing and pulling and tearing and cutting of silicone made skin substitutes, etc… The morbid and fetishistic attraction with skin and flesh was everywhere. The workers featured in the film remained silent, and most of the time they were also pictured as body parts: hand that shape matter, robot-like. Occasionally there was a glance of a factory worker at rest, sipping his noodle soup in between of pink silicone carcasses. The film documented how sex toy dolls are made, but it did not reveal anything about the working conditions or context of why this should be important to see or discuss. In the contrast to the other two artists, where I could picture somewhat their beliefs or artistic approach, Lash did not make me feel to know anything about the artist: What is his position, interest, approach… only plastic flesh fetish.

The “solo exhibitions” brought up the always present question for me again: how do you discuss something ever-present that you are in the middle of, and that provided you with the tools to discuss it? And when the artistic products circulate in a scaled down caricatured version of capitalist exploitation – the art world – it adds yet another layer of questions to the already ambiguous messages the artworks express.