Hong Kong, 5pm September 29, 2016, Creative Media Colloquium

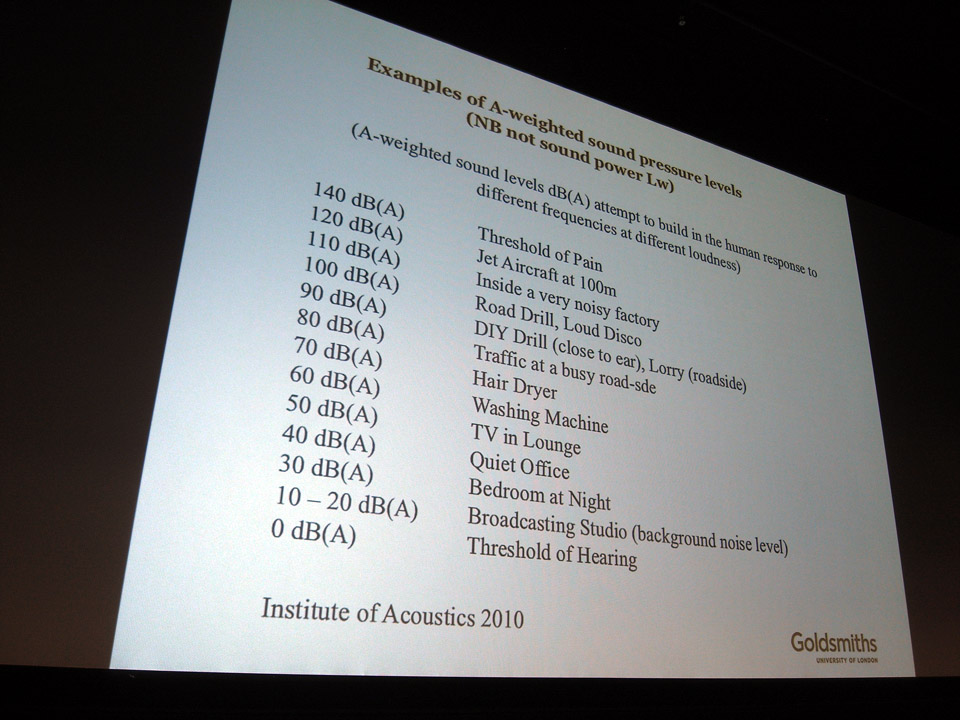

Drever is a sound artist and professor at Goldsmiths, University of London. The major part of the lecture took place at a rapid speed with references raining in the intervals of seconds. At moments it seemed – in the words taken from one of Alan Kwan’s artworks – that his mouth failed to keep up with the speed of his thinking, resulting in snippets of unfinished sentences left floating in the air. He talked about sound intensity, and how it is perceived differently by different listeners. Apparently there even seems to exist an array of diagnoses for people who perceive sound differently: increased sensitivity to sound, sensitivity to specific frequencies, etc. Even during a person’s lifetime the way how one hears changes according to one’s age, personal and environmental circumstances and predispositions. It is a complex field, as perceptions are always individual. Can there be a shared experience? The main point of Drever was that in a similar way as people diagnosed with autism call for a greater tolerance of “neurodiversity” – we should consider the “auraldiversity” of our ears. This argument goes back to the phenomenological school stressing the value of individual experience, as well as Foucault’s theses on “normality” as a social construct. So yes, each of us hears slightly differently, and this should be, according to Drever, taken into account when designing our environment.

From here Drever moved on to his specific research interest, the sonic qualities of electric hand driers located in public toilets. His main claim: they are too noisy, to such an extent that it can cause trauma and/or pain to sensitive persons. Taking this everyday object as an example, the difficulties of acting on auraldiversity became apparent. How does one define what is and is not “normal” when there is no norm, and the only measurement is one’s subjective perception? The judgement, unsurprisingly, seemed to enter an aesthetic realm, where the likeability of a sound depended on personal affect instead of a technical measurement. A serious mishap took place during the process of almost fetishistic fascination with lavatory hand driers that Drever has developed. Based on the first part of the lecture I had expected him to propose some personalized solution to combat, transform or divert the hand drier sounds, some kind of sonic variant of the image fulgurator. Yet instead, his fascination with the sounds these machines produce resulted in a total identification with the hand driers: Drever lovingly recorded their sounds and arranged them into hour long compositions. He even had a project where he made people vocally imitate the sound of the hand driers. He even made his own children sing out lout the hand drier’s brand names. This was pure dada. Nothing wrong about that, if it was presented in the context of noise music, where the fascination with noise and its neurophysiological effects take a central role. But torturing an audience with an hour long auralnormal (standard) recording of hand drier could hardly be seen as a response to the problem discussed in the first part of the lecture. He himself acknowledged this paradox, and unsurprisingly, all audience questions focused on this issue too. It remained unresolved, and worse, it diminished the noble goals outlined in the beginning of his presentation.

Despite, or maybe because of this paradox, the lecture provided ample food for thought. How come people complain about noise, but at the same time cannot stand absolute silence? It is probably a parallel to our social behavior where we on one hand feel abandoned when we are alone for too long, but can feel overwhelmed if constantly surrounded by too many people. Not too much, not too little. Sonic norms and measurement units are nothing more than an agreement on technical measurement procedures. They can hardly capture the elusive individual experience of sound or its impact on one’s senses and body. Same as legal norms, which exist to prevent crude damage to body and property, but cannot prevent dickhead behavior. This talk exemplified how becoming sensitive to the nuances of sound can be both an aesthetic blessing and a psychopathological curse. Closing one’s eyes is an option, but closing one’s ears is not.