Hong Kong, March 19 – May 29, 2016 http://www.para-site.org.hk

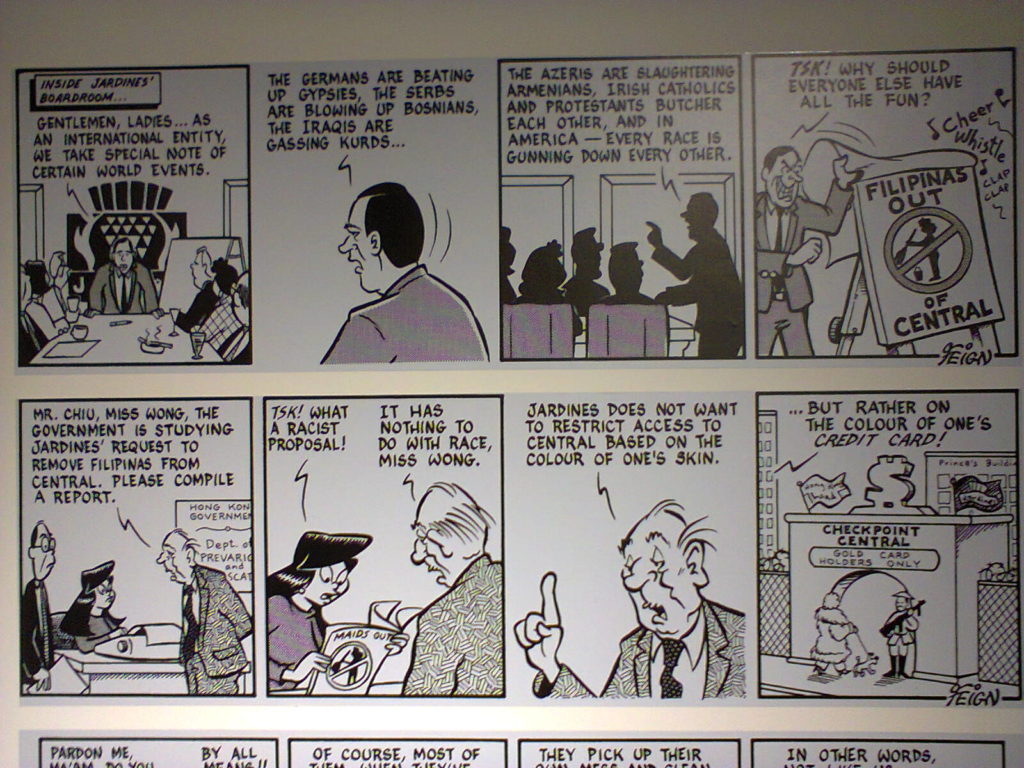

The main theme of the exhibition was the population of domestic workers in Hong Kong, as well as the more general topic of economic migration throughout the Asian region. The exhibition was quality and dense, as can be expected at Para Site. It took time to walk around and take things in. But that is natural with the wealth of exhibits and information present. Compared to the inaugural show last year, I felt that the curatorial team (Freya Chou, Cosmin Costinas, Inti Guerrero, and Qinyi Lim – quite a lot of people, this could have been a biennale curatorial team!) became better acquainted with the space and the placement of individual artworks felt more relaxed and less crowded. A blind spot which remained from one year ago was the center of the main space: Last year there was a strange fish-tank sculpture, and this year there were some miniature paper cutouts inside of protective glass covers (Ryan Villamael, Isles Series II, 2014) on white plinths, which again looked somehow random. But that’s just a detail.

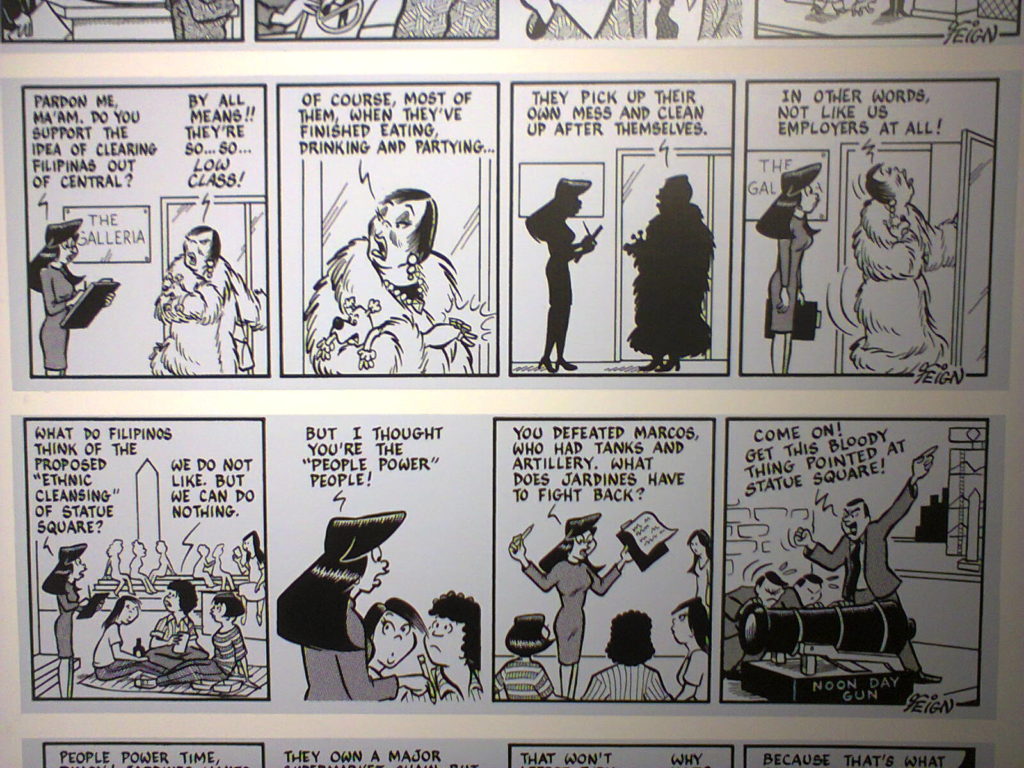

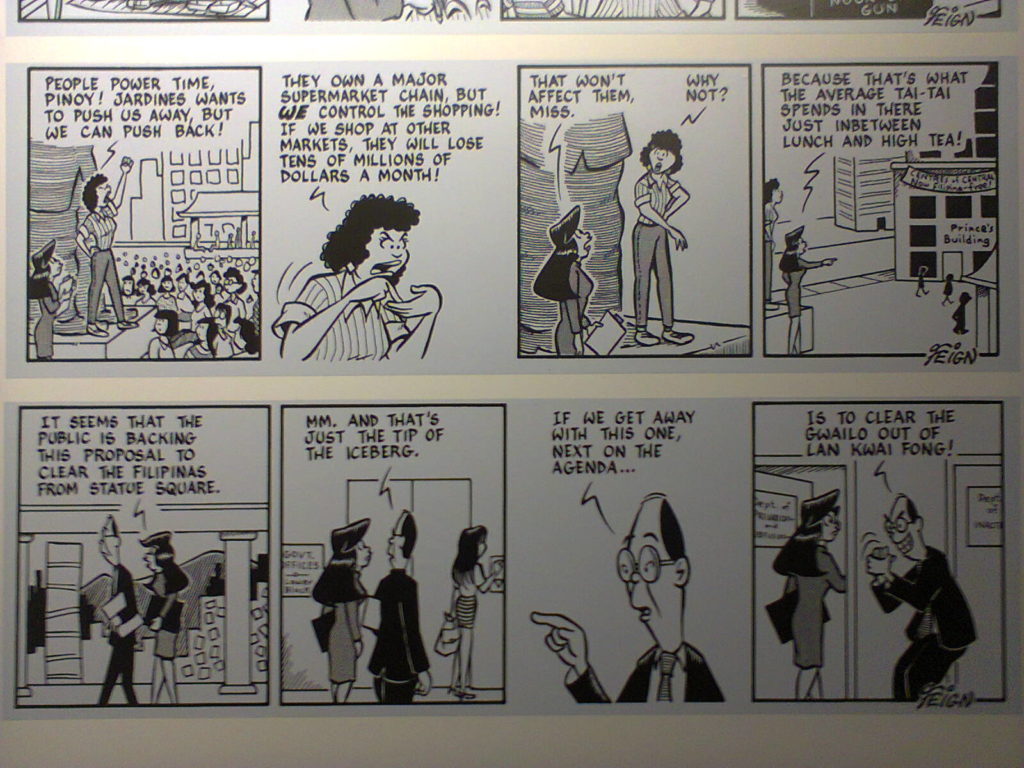

Overall, the show felt comprehensive, and it was taking up a theme that is very much visible every day (Filipino and Indonesian domestic workers are everywhere in Hong Kong). This was an easy topic to relate to, as it is so close to the everyday life, yet at the same time, these workers seem to live in a parallel universe even though we share the same overcrowded living space. I got a feeling that Filipino’s were present in rather large amount, while Indonesian Muslims’ were underrepresented. I am always curious about those fully veiled Indonesians, as that’s something I did not get to see during my growing up time in Europe. But their veiling seems to be not only a way to conceal their bodies, but also their lifestyle, in contrast to those who like to organize beauty contests and dance parties as one of the video-works showed (Koeken Ergun, Binibining Promised Land, 2009-2010).

She show was also a good opportunity to reflect on racial stereotypes and racism in general. I myself learnt what racism meant after I moved to Asia. Reactions I encountered ranged from being approached as a white half-god, to a walking moneybag, a barbaric outsider who needs to be taught local customs but who will never understand anything anyway, a dangerous pervert rapist or a descendant of a nation of heroes who saved the country. So I can a bit relate to how it must suck if a whole nation’s identity is that of disposable cheap domestic workers, basically modern slaves. The exhibition worked successfully against these stereotypes, while leaving enough reminders of the dire and sad racist neocolonialism that permeates society in Hong Kong, as well as many other places.