Seoul, December 3, 2015 – February 14, 2015, http://plateau.or.kr

I have been a fan of Lim Minouk since I saw the “S.O.S. Adoptive Dissensus” video in a group exhibition in Ilmin Museum a couple of years ago. It was a work which stood out among many others. I read through some of her catalogues, and saw other works in a similar vein – dealing with topics related to the sore spots of Korean history as well as of the present Korean society: The Han riverbank redevelopment, the gentrification of Yeongdeungpo, the story of South Koreans wrongly accused and imprisoned as North Korean spies for political reasons, the unattributed human bones remaining after the Gwangju massacre, etc. The form was oscillating between theatre and performance, sometimes with specific sculptural objects involved, all documented on video. The aim seemed to be a breaking down of the boundaries between fiction and documentary, between the “official” history and personal histories. Being part of any of these performances must have been an extraordinary experience, but even in the video format, they remained powerful artworks. All this made me very much look forward to her solo show at Plateau (affiliated with the Samsung chaebol).

The first artwork at the entrance to the show was a gate made from containers, echoing the permanently installed Rodin’s Gates of Hell, accompanied by a melodramatic soundtrack of old Korean radio hits. The main exhibition space consisted of three separate halls. Hall one was darkened and with theatrical spotlights. The biggest object was a huge wax sculpture merging South- and North Korean mountains and two respective landmarks. Then there was a set of “portable keepers”, sculptural objects that have been featured in some of Lim’s video works. This room also featured a mini-retrospective of the video works I mentioned in the introduction of this article. Their installation was the biggest disappointment of the show and made me very sad: About 8 TVs in one long cornered row, without any sound. These were the works that were key to Lim’s artistic development, but here they remained mute, condensed to a patchwork-like decorative video installation. I will return back to this point later in the conclusion, as the muteness of Lim’s key works became a key moment influencing my whole perception of the exhibition.

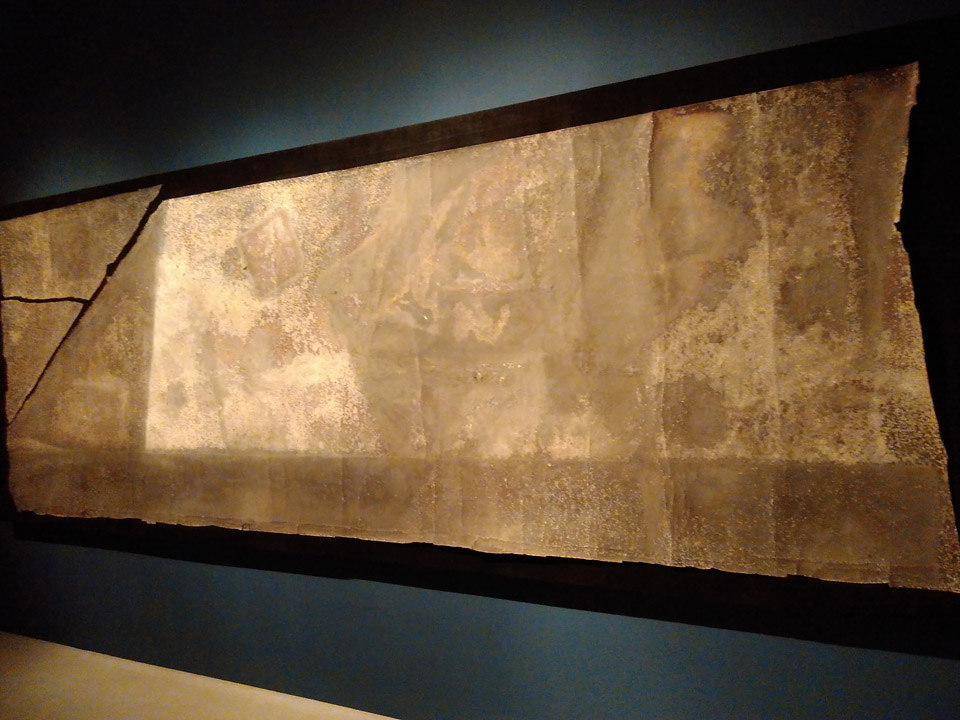

On the other hand this room also featured two works, which were the most intriguing even though I could not decipher them completely. It was two large flat ‘canvases’: One seemed to be made from vinyl and the other from a large roll of floor linoleum. Both were covered with dirt, hinting that they have been salvaged from some redevelopment construction site, but maybe not. One of the works further contained a crooked wooden stick that looked like a walking stick made from a tree root. These two works reminded me of Josef Beuys’ works, where material itself is exhibited as a signifier for the energy it contains. Here the dirt-covered objects, stripped of their original function as covers, still emanated a protective energy and inseparable connection to their place of origin (the floor, or roof of a torn down house) that could not be taken away from them. And then there was the walking stick, which I took as a direct reference to Beuys, who also used it on a number of occasions.

Another room had a double projection, featuring a reedited version of a South Korean TV program allowing citizens to search for their relatives in North Korea. It was all in Korean without subtitles, but I could understand enough to grasp that it was a reference of a very emotional event in South Korean history, not unlike the nostalgic music played at the entrance to the exhibition, as well as a reference to the aforementioned wax sculpture of South and North motives, which all these people wished melted one day back into one.

The last large room, with daylight, featured a strange stage-like setting with Yang Haegue-like sculptural assemblages, which however were anthropomorphic: objects-sculptures combined from different soft materials (cloth, fur, felt,..) and hard objects used in TV journalism: a TV camera, a zoom lens, etc. All these “actors” were turned towards a large container-cum-billboard lined with bright lightbulbs, but simply featuring a door and window (as one would see in repurposed containers for living) instead of an image. I understood that container made-object in this room should probably provide a link with the container-made gate at the entrance, and I also understood that the work is a referencing the role of media and mediation in some way, but it did not seem to go beyond a vague reference to these topics, allowing everyone to think whatever s/he would like.

Now after a quick rundown of the show, it’s time to draw a balance. I identified three thematic circles in the show.

First was the idea of mass media and mediation – present in the form of the container entrance gate (with samples of old mass media content) and linked to the concluding ‘media room’ sculptural installation. It was a good way to delineate a beginning and end of the exhibition, and state the fact that ‘media representation influences our perception’. But in itself, this message seemed a bit too generic.

This theme linked into the second theme – the North and South Korea issue – present in people’s minds as well as in the exhibition through mediation via the two channel video of Koreans searching their relatives and the large wax sculpture of two Koreas. These works only added to the pile of other 70’s anniversary of Korean liberation art projects (MMCA’s Uproarious, Heated, Inundated, SeMA’s NK Project, Samuso’s DMZ Project, Seoul Photo Festival’s SeMA BukSeoul exhibition), but they did not offer any new or critical position, only a bittersweet longing for a dream that is slowly fading away, as the old generation dies out and the young generation does not care.

Third was a barely audible whispering of all the great artworks that Lim has created during the previous years, but which were largely removed from sight. There has been a strong presence of Portable Keeper objects, however they were presented as sculptures in glass vitrines, stripped of all their meaning and hardly traceable back to the performances they have been used in. The aforementioned mute videos were the only artworks referencing the core body of Lim’s work, and in the end, their muteness became a metaphor for the problem of this whole exhibition: Lim’s work, which has often been critical and politically charged, has been completely sanitized and stripped of any controversy in this show.

If one considers the fact the exhibition is taking place at the expense and in the location of one of the major corporations in Korea, also heavily involved in construction and development (addressed critically in numerous Lim’s works), and very much prospering under the reign of president-dictator Park Chung-hee (a time of political persecution and imprisonment of opponents – addressed in Lim’s Firecliff_2), it becomes obvious why this muting of Lim’s works happened. The question that remains open is why Lim allowed this to happen.

Was this a case of ‘recuperation’ – the assimilation of an opposing view into its opposite (as has happened with a lot of leftist slogans employed as a justification for capitalism, e.g. the ‘sharing economy’)? Or was this a straightforward sell-out of the artist, bending her back for fame and income one she reached the ‘glass ceiling’ with the work she was doing? Or has this all been an elaborate Samsung-funded viral marketing campaign from the very start of Lim’s work? It is hard to not be disappointed in the perspective of Lim’s previous work.

I felt sad and empty leaving the show. It is definitely worth a visit, but first familiarize yourself with Lim’s previous work. Maybe this show is the ultimate argument why artists should not attempt to balance on the slippery edge of politics and aesthetics – sooner or later, they will age or they will get hungry, and then they reach out for the cash/fame, and they slip. Once they slip, they have no ground beyond their feet anymore, and all that is left is hold on to what they reached out for. The Korea-specific circumstances are another thing to ponder over: In this strictly hierarchical society, where a few billionaire-family owned corporations control all influential positions, what is the career path of an artist critical of the politics and ‘development’ that the rulers have kindly outlined and implemented for the whole (and for the ‘good’) of the Korean society? Thus, in the end, this show again opens questions, not dissimilar to those opened by Lim in her previous work. Only this time, these questions are directed at Lim’s own artistic integrity instead of the subject matter presented in her work.

I wish this is some misunderstanding or a one-time slippage from which Lim can recuperate. The problems of the current exhibition do not diminish any of her prior diverse and strong oeuvre.

Maybe at the very end it would be good to mention Joseph Beuys again. Beuys was an artist of many media, from sculpture to performance, and he was also very active politically on the left side of politics. He managed to keep his work aligned with his political activities, not making compromises, and it was possible, because he always stayed on the metaphorical level, talking about energies, materials and healing, about universal human values of liberty, equality, fraternity. These are the ultimate goals that people strive for and can agree on. His works were a materialization of and reference to these energies and ideals, and his political activity was a transformation of those into another form he called social sculpture. I saw a hint of this direction in the aforementioned wall-dirt works of Lim. Those were the only works that survived the semiotic sanitization and sterilization process Lim’s work has undergone under the Samsung roof for the sake of making this exhibition. These works survived because they did not contain any literal references, yet were laden in metaphorical references which are much harder to erase, as they emerge at the intersection of the work and the viewer.