Prague, July 22 – November 15, 2020, https://matterof.art/

I have visited the show right during the opening week. The show is spread across two main sites, the Prague City Gallery on the top floor of the Municipal Library Prague, and a couple of industrial style ex-market halls in the Holesovice (Prague) Market. The visitor guidebook was not yet available during my visit, so I navigated both sites with little prior knowledge, except for the introductory blob on the Biennial website. The overall theme attempted to cover themes like gender/race inequality, feminism, care, labor, etc., and how artists can comment/contribute to the discussion.

I started my journey in the Municipal Library, where the clean evenly lit space offered a well arranged selection of works in a pleasant environment. The artworks for me fell into three categories. Some were too obvious, some hard to get (“gallery style”) and then a small part that struck the balance and managed to convince. Overall, I felt that the too obvious artworks were in a majority, but maybe there was a specific logic behind that given the stress on equality, access and care that the show had.

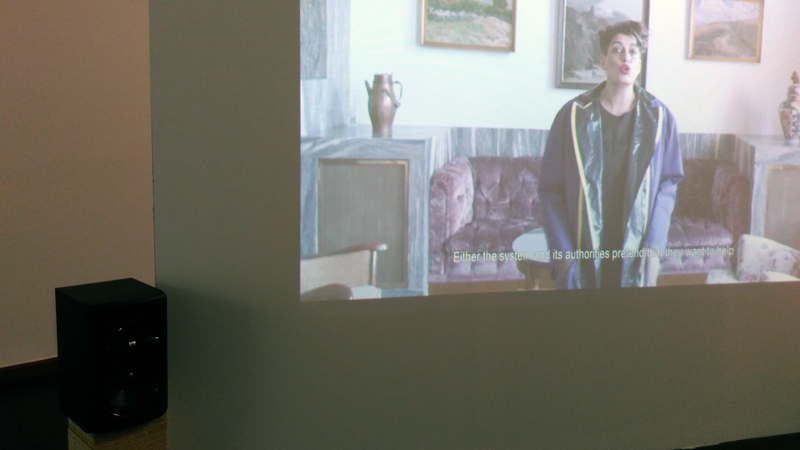

The video-artwork welcoming visitors featured a Roma human rights activist giving a speech in a highly aesthetic modernist villa (a museum site today) backdrop: “They say they welcome you, but they want you to leave as soon as possible”… attempting a parallel between Roma as “visitors” and “visitors”.

A notable, repeatedly appearing element were artworks from the second half of the 20th century from the collections of the Prague City Gallery. Works by Adriena Simotova are pulled out every time something “fragile” and “feminine” is needed (compare with last year for the “Carnations and Velvet” show at the same location). Alena Kucerova’s graphic prints are a bit less gentle, but the gentleness appears at the intersection of the bodies displayed and the metal-plate puncturing that gave birth to the matrix. Eva Springerova and Vera Merhautova were another two female artists (sculptors) whose works were hauled from the depots for this show, and so was Sonia Natra´s bust of a “Czech Girl”. The curators explanation was that they attempted to emphasize the “care” that a museum is delivering to artworks instead of the “just colonizing the museum in one direction with newness.”

I more appreciated the newness, e.g. in the drawings by Otty Widasari that appeared to arrive from a very recent past of the last months with ink still almost wet on them. First I thought they related to the black-lives-matter protests, but in fact they were documenting the arrest of a prominent Indonesian crime boss.

One subset of artworks ventured away from art and closer to real life. Alice Nikitinova showing drawings done together with or for her child. (I did not get much from them, but I guess that´s fine as I was not the target group anyway.) Viola Jezkova´s tragicomic video, from which I remember the scene with a crying child and poor sleep-deprived husband. Or – on a different note – the collection of flint stones from the open-air museum of folk traditions and crafts in Bolatice (Jirí Dudek).

The video, and generally speaking, the artwork that touched me the most was Eric Baudelaire´s “Un film dramatique”, shot not by Eric Baudelaire, but by kids from a Paris city suburb. Maybe it was because it had the most comfortable seating (IKEA Knopparp). Maybe it was because Eric Baudelaire gave the camera to the protagonists and let them to a big extent shoot the film themselves. There was no aestheticizing and dramatizing, there was no formalism. There was no telling and explaining, except the telling and explaining the protagonists themselves did. It was not easy to follow, but it was real and honest, touching on the themes of empowerment this show was saying it was addressing, and not just commenting on or telling something about it.

Sometimes the curatorial hand was just too heavy-handed, for example when the white marble sculpture of a “Czech girl” (Sonia Natra) was placed “looking” directly at the paintings of “Gypsy workers” (Bohumila Dolezelova), with stereotypical rice field straw hat Asians depicted in a social realist woodcut fashion peeking around the corner (Taring Padi Collective – posters contained a lot of text, but no translation was available).

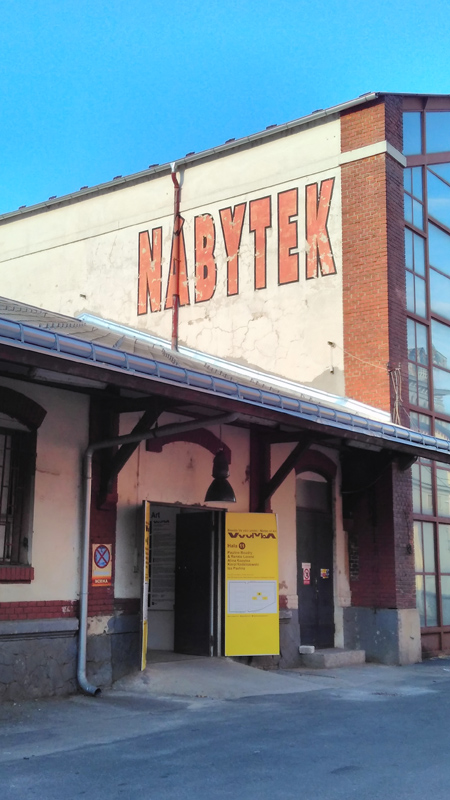

In the other exhibition venue in the market halls (side by side with actual market stalls selling cheap fashion and suitcases run by Vietnamese immigrants), I was welcomed by an installation of a simple “shelter” from empty plastic transport boxes (used often in market stalls) combined with a video telling some “story from life” of a Vietnamese living in Czech republic. The artist (Tuan Mami with Minh Thang Pham) might have had good intentions, but my subliminal reaction consisted of an uneasy shivering in my neck. The fact that the artist appeared to be of Vietnamese descent made me feel even more uneasy. It suggested that he created this work in order to cater to the tastes and expectations of the curators of this show, which in all their goodwill slipped into fixing the stereotypical image instead of breaking it while discussing the themes close to their heart. This in turn reminded me of those real stalls next door, where stall owners where doing something quite similar, supplying textile products fitting the demand of the local audience – I mean customers – that had little interest in the sellers lives, but were rather interested in the agreeable price and good function. Maybe that was the reason a fridge with “Saigon Beer” was included in the installation.

There were a couple of video works at this location too. Jiri Zak’s “It Was Probably Our Karel, She Said” attracted my attention through the precise cinematography and dramatic performance of the main actor, and I also appreciated the grounding in a local, slightly obscure context.

Another big hall was almost exclusively dedicated to sexuality, from Iza Pavlina painting for tips with a vibrating dildo on xhamster live, to embroidered bedsheets with stories from sex workers lives (Alina Kopytsa), to a large size projection of a queer performance-cum-political statement (Pauline Boudry, Renate Lorenz). Extremely enlarged children´s drawings from an artist´s (Karol Radziszewski) troubled pre-coming-out childhood were watching guard over this assemblage of works.

The last hall, also including the book shop, featured a large scale installation, attributed to the Mothers Artlovers collective, who created the installation together with their kids during a workshop. It was colorful, but well arranged, and it clearly showed the art-awareness of the mothers by steering away from stereotypes and presenting an inspiring and wholesome environment as convincing as if one of their white male peers (husbands) would have done it.

I very much appreciated the off-site nature of the second location where art and daily life mixed. Where you could buy a sausage and a drink – or a cheap China-made suitcase – on the way between two exhibition halls. The Biennial consisted of other smaller off-site installations, which I sadly did not visit. Maybe they would offer more of the freshness and local connection that I felt when walking around the market stalls.

On the whole, I found the show well directed and worthy to see. As mentioned, there were moments when the explanatory nature of curatorial arrangements, or the representational and explanatory nature of the artworks themselves got into my way, but this effect should not be overly stressed. I guess it might have also been a balancing act between delivering an accessible and inclusive exhibition storyline that would not be too academic to exclude those concerned. I feel that with more time, and more engagement, each of this moments I experienced could be the beginning point of a discussion that could also move the discussion in the right way towards the intended goal.

The overall experience was smooth, I slid through both locations without issues, and there was enough material to take in. When I browse now, after the visit, through the PDF version of the guidebook that was made available in the meantime, I feel the same smoothness and ease of use. One can clearly see the effort that went into organizing the show and creating this experience, even under the probably limited budget and corona travel restrictions.

Lastly, I wonder what the future of this Biennial will be. Will it really be a “biennial”? Will there be a second edition in two years’ time? Biennials come and go in this part of the world. There were many not-so-successful ones. VVU-MOA – with its slightly weird name – decided to focus its resources on a smaller scale, yet providing a quality product with fine-tuned details like a visitor guidebook and a nicely designed reader in Czech and English. It is a good start and I will be looking forward to what comes next.