Vienna, March 31 – May 28, 2017, http://www.q21.at/

Curator: Sabine Winkler, Artists: Antoine Catala, Xavier Cha, Florian Göttke, Femke Herregraven, Hertog Nadler, Micah Hesse, Francis Hunger, Scott Kildall, Barbora Kleinhamplova, Tom Molloy, Barbara Musil, Bego M. Santiago, Ruben van de Ven, Christina Werner

This was a very hot exhibition. I was excited that it took place at MQ, and it brought a bit of life to the adjoining spaces which are more on the traditional side of contemporary art. This exhibition directly addressed latest social issues, it was reacting to something taking place outside and around it. Each of the artists was concerned about something that touches his life. The exhibition also came across as very curator-driven. There was a very clear concept what this is all about: Emotion measurement, analysis and manipulation using technological tools. The artists in the show were mostly emerging ones, which also brought freshness to the show.

There was also a downside to the focused curatorial approach: Some artworks came across almost as illustrations for the curatorial concept, especially in combination with descriptive statements explicitly explaining what the artists tried to express. And the artists themselves occasionally slipped into the realm of well-known clichés of neoliberalism-blaming or conspiracy theories. But it is not easy to talk about and analyze complex phenomena as they occur, so one has to respect that the artists took up this challenge, even though their knowledge might have been limited by their own filter bubbles.

In aesthetical terms, the artworks presented another dilemma: How to visually represent complex abstract topics? The two extremes were visually captivating presentations with little content to communicate (aesthetic ready-mades) and on the other side rather boring presentations of intellectually challenging projects. The presented artworks hovered between these two poles, and it was hard to find a favorite that would somehow be able to bridge both sides.

Tom Molloy’s Protest (image above) was the most striking work in terms of aesthetic appearance – hundreds of protester photo cut-outs arranged on a long plane. Yet behind the visual complexity and beauty, the algorithm was rather simple: source protester images from on-line sources and news media, print out, cut out. The work reproduced a recurring media image type in a very beautiful form.

Scott Kildall’s EquityBot (image below) was very complex on the inside, and I found it one of the best works conceptually and technically. Yet within the exhibition space, the presentation was more like an advert for the actual work than the work itself. How to meaningfully exhibit a creative algorithm at work remains a question.

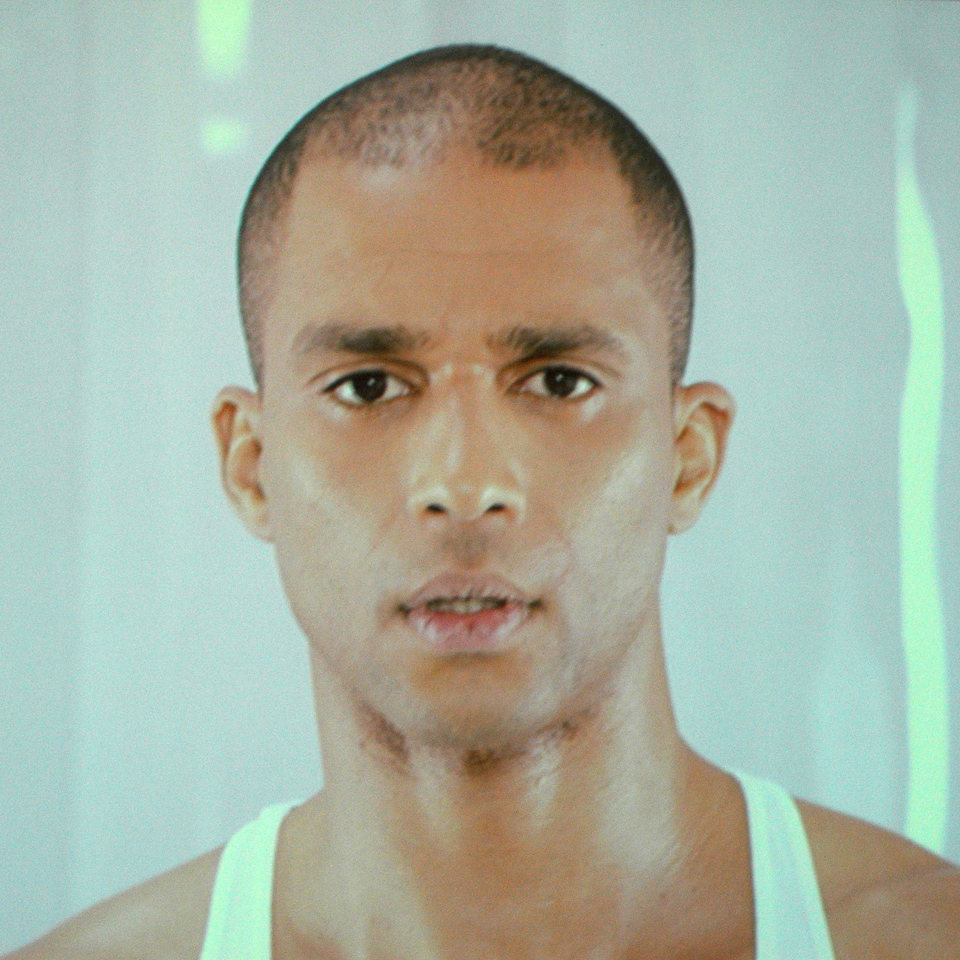

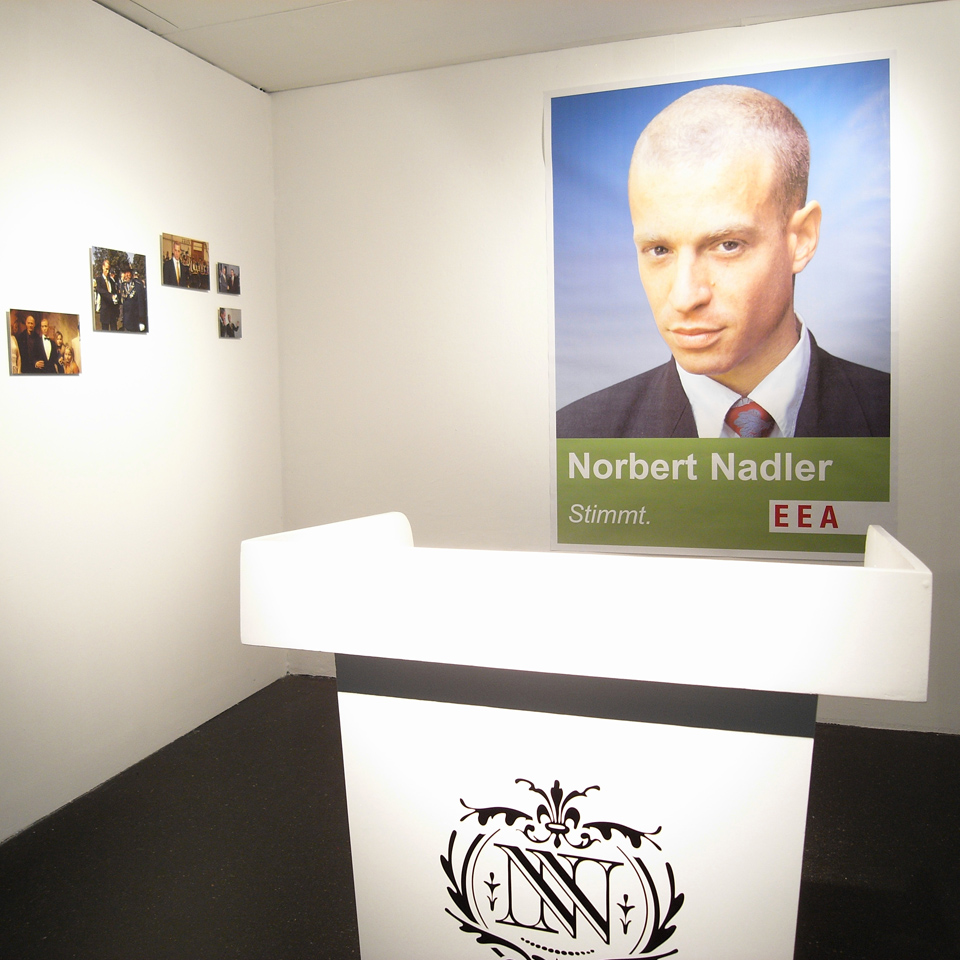

Other artworks were somewhere in between the aforementioned two. Three artworks created a connecting line for me by featuring a close-up of a head, and a fourth one by making use of the visitor’s own head: A video of an Emobot Teacher (virtual avatar driven by human face recognition, by Antoine Carala), a video of actors performing a fast sequence of different emotions (real face expressions driven by fakeness, Abduct by Xavier Cha), a fake politician campaign (a real actor driven by fakeness, Stimmt by Hertog Nadler), and lastly Emotion Hero by Ruben van de Ven, which somehow completed the circle and extrapolated the positions where Emobot Teacher and Abduct stopped by offering the visitors a tool to train their own emotional face expressions. Emotion Hero gave the visitors a choice whether to submit their own face to the application or not. I appreciated the option of simply walking away, a luxury that we might not have once the feature is implemented within some teleconferencing software or supermarket shelve advertising display. Welcome to the future.

The special bonus of the show was the curatorial essay by Sabine Winkler in the exhibition booklet, really worth reading.