Hong Kong, January 15 – February 14, 2016, http://www.floatingprojectscollective.net

Floating Projects is a new space in the South of Hong Kong Island in Wong Chuk Hang. The place, which is run by a group of artists, is a combination of a cozy coffee shop and an experimental art space with a laidback atmosphere.

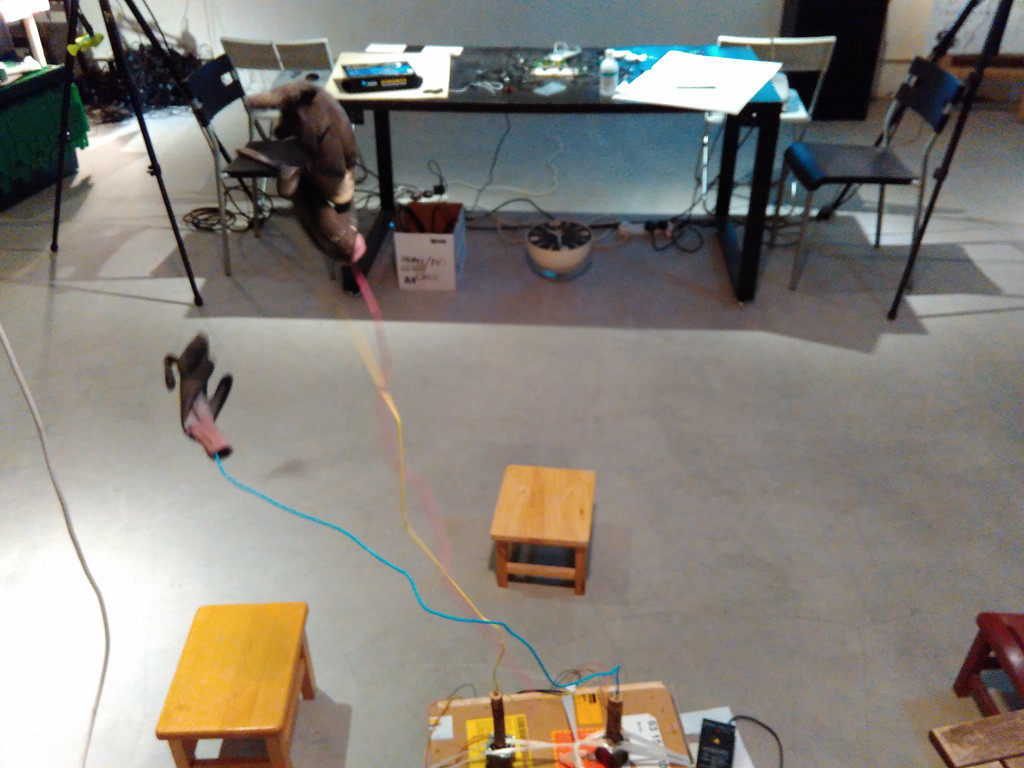

Wong Chun Hoi’s exhibition has been the first solo show in the space. Upon entering the space the visitor encountered an assemblage of cables and switches which looked most of all like some work in progress. Switches for what?

It turned out that the switches itself were the artworks. Connected into seemingly endless chains, these where switches for switching, a bit like the ‘art’ in the “l’art pour l’art” statement. The thing to be observed by the gallery visitor was by itself the unwanted side effect of the switching-for-switching’s-sake-process: the clicking of the relays, and the imagined energy spent on the process of switching. At the end of the switch chain, there usually was an end effect to observe, like a moving miniature mechanical fish or a LED light, but these objects were mere indicators, mere appendices to the monstrous switch chains that preceded them. The clicking of a switch is usually something that is ignored rather than focused on, but in this work, the click of the switch became the main actor, almost as musical instrument.

Another work in the show was good at soliciting attention: A number of construction gloves attached to the ends of thick bent isolated wires shaking violently. The movement of the gloves made one’s eyes naturally move towards it. While the switch chains (“hardworking circuits”) were most memorable for their sonic dimension, this work was most suitable for being looked at: A kinetic sculpture.

During the opening, a performance took place, in which two volunteers from the audience where asked to play a ‘game’ that consisted of giving each other mutual electric shocks through pads attached to the body: If one person pressed a button, the other got a shock, if no one pressed a button, both got a shock. A game for true masochists.

What to make out of these works? The title ‘hardworking circuit’ implied a personification of the electric circuit. This personification (and also cute-making, as is often the case in Asia) of things seemed to relate to an animist belief – a life of things. This belief in the life of the unalive was also expressed through the gloves shaking on the top of wire sticks – a ghost-like human presence. The electro-shocking game was an attempt to include humans in the electric circuit – the human as an unpredictable component of a system rather than an actor in itself. These indices pointed to an underlying post-human belief, or maybe subconscious fear of the post-human world: A world of circuits and machines, where humans are nothing more that switches or triggers of processes that have overgrown their own designs.

The crudeness of the works was stronger than the cuteness. These were no robotic dogs or Tamagotchi pets. These were intestines torn out of a building’s electrical room belly: Alive, pulsing and strangely autonomous.