Seoul, October 14 – 18, http://goods2015.com

One week after the main Korean art fair KIAF, which I unfortunately missed, Goods opened. Goods is the first instance of an alternative art fair, where artists sell works by themselves.

One week after the main Korean art fair KIAF, which I unfortunately missed, Goods opened. Goods is the first instance of an alternative art fair, where artists sell works by themselves.

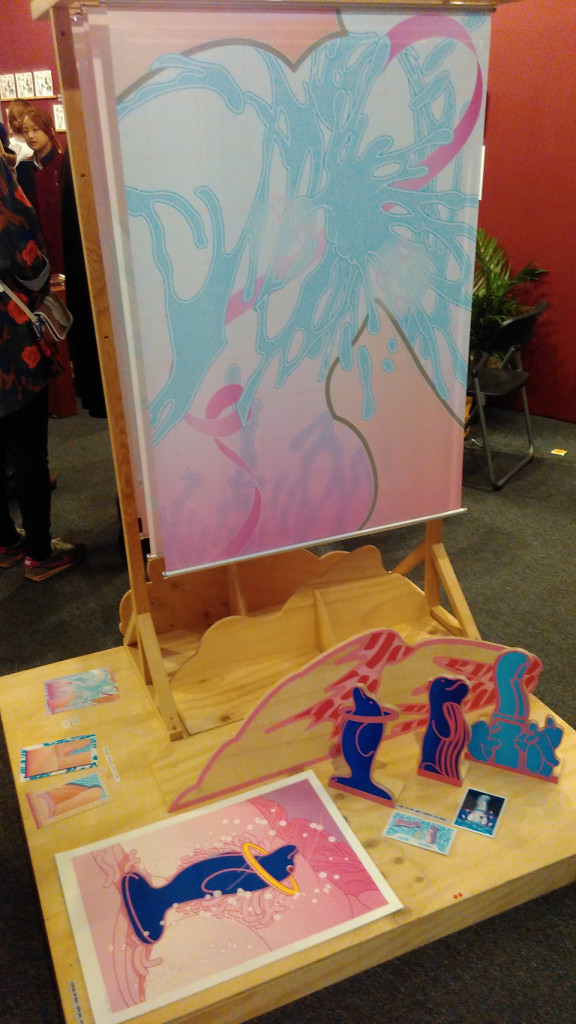

The style and kind of the artworks seemed to follow a certain pattern that could be described as manga-anime and sci-fi inspired post-internet art, but there were also outliers which made the whole more interesting. The selection of artists seemed to echo the works that could be seen at the Ilmin Museum’s “New Skin” and “Space Life” exhibitions, as well as all Common Center’s exhibitions (“Autosave”, “Fujoshi/Zeewoman”). It all seemed to be a certain group of people with a certain aesthetic that was behind the aforementioned shows as well as the fair.

There were a lot of small size works, prints, etc. The prices (prices displayed on labels) ranging in 10 thousands of won for small multiples, to 100 thousands of won for paintings, drawings or sculptures and a few larger works that passed the 1 million won mark.

Goods seemed like a mixture between a DYI art fair, an anime con and a flea market. The atmosphere was relaxed, and it was good opportunity to meet and talk with artists themselves. The overall impression depended on the visitor’s attitude to the specific aesthetic featured. It was a fun event for those who felt close to the aesthetic presented, and for those not familiar, it was a small universe to explore and wonder at something strange and new.

When talking about these events with someone, I often heard the word “subculture” or “alternative”. But alternative to what and in which context? Within the art market standards, Goods is indeed an alternative to the gallery-run art fairs, opening up direct channel between buyers and sellers. Unfortunately until today, I have not come across any example where this model would generate comparable financial results with the gallery-based model. That however does not speak against it the artist-run model. In the end, financial results is not the only benchmark to compare (even though for any event where sales are the objective, this should be the main metric). Community building is probably as important as sales.

Generally, the challenge is how an association of artist-run and non-commercial art spaces can put together an event where the main goal is selling art. How to conduct “mainstream” selling while staying “alternative” and “non-commercial”?

Another part of the story unfolds when one relates the world “alternative” to the actual contemporary art context, the art historical context. Looking at the artworks presented in the fair, one can refer to the previous posts on this blog regarding the aforementioned exhibitions (1, 2, and 3). The question is what is “alternative” about works that draw on on-line culture that is the mainstream for the generation of artists producing these works. What is alternative about youtube fan videos and afreecaTV live streams referencing directly or indirectly manga/comics/computer games produced by big entertainment companies? Not to mention the “pre-conditions” leading to this subculture’s emergence, i.e. the fact that a lot of this takes place on mainstream on-line platforms of billion-dollar valued corporations that make money from every click a user makes. Can this kind of content, existing thanks to these kind of communication platforms be called alternative?

Two arguments support the doubts whether these artworks can be called alternative in terms of content: One, the on-going post-internet art phenomenon, which has already entered the mainstream gallery world today. Two, the already successful appropriation and transposition of this ‘subculture’ into the mainstream, all the way to LV bag design by Japanese artists like Yoshimoto Nara, Takashi Murakami and other Kaikai Kiki “superflat” artists.

Additionally, I have observed a bandwagon tendency, where artists seem to produce works that fit the ‘alternative’ and ‘subculture’ labels simply for the sake of fitting in and being part. Even if it has been a ‘subculture’, this is one of the signals that transformation from ‘subculture’ to ‘mainstream’ is taking place. Unfortunately Korean cultural characteristics seem to reinforce this tendency.

Lastly, it is of course important to consider the local Korean context. Here, the art world seems to be a bit stiffer and slower than elsewhere, which is due to the government funding (government administrators are usually stiff) and the gallery world dominated by big conservative corporations both on seller and buyer sides. Within this context, Goods makes perfect sense. It provides a platform for artists which have nowhere else to go but the growing network of independent artist-run art spaces. It is then a logical step that Goods emerged as a place where independent artists and organizations can interact, and hopefully attract the interest beyond their regular audience-friends circles.

On the whole, Goods presents a position which is very much needed in Korea. It may not be that alternative or subcultural as the artists and art spaces that come together in it, and it may be balancing on the thin line between being non-commercial and selling (with each participating artist offering a different response to that), but it did succeed as an event that brings a new position into the Korean art scene, and for that one can only thank the initiators and look forward to next year’s follow up.

1 comment for “Goods 2015”